The future of sports may sound very different. It’s hard to imagine professional sports without roaring crowds and cheering fans. Looking forward, how can technology and design be used to bring back the noise?

In a recent blog, engineering and consulting firm Arup investigates what professional sports will sound like in response to Covid-19. Whether it’s introducing “streamed” virtual fans through stadium speakers or adding artificial crowd noise to broadcasts, stadium soundscapes have an uncertain future. Arup’s acoustic and audiovisual designers are not only exploring how to adapt fan-generated noise in stadia, but also re-envisioning a more inclusive, accessible experience for all.

And the crowd went silent

At least as far back as ancient Rome, spectators have clapped, cheered and booed to encourage the home team and intimidate the opponents – a phenomenon we at Arup have studied for years, in order to enhance the acoustics of live sports. Since the Covid-19 lockdown, however, stadia around the world have gone silent. And while sports leagues are now reopening, it’s to a changed sonic environment devoid of the fans who give matches energy and personality. One example can be found in the German Bundesliga, which resumed on May 16 to reports of an echoing, eerie, and sterile atmosphere, while players claimed to have found the games lacking in urgency.

How can teams, leagues, venues and broadcasters bring the noise back without fans in the stands? Some have already begun to experiment. Taiwan’s CTBC Brothers installed robot drummers at their stadium, Denmark’s AGF Aarhus streamed live video and audio of fans sitting at home onto the field, and after broadcasting the first games in near silence, the Bundesliga now gives networks the option of adding in artificial crowd noise. Reaction has been mixed, with some commentators welcoming the noise and others bemoaning its artifice.

Bringing back crowd noise isn’t a straightforward task. Novel, quick-fix solutions may be attention-grabbing, but risk distracting and alienating fans. It’s going to be impossible to perfectly simulate a real-life, full-capacity crowd, but rather than seeing this as a limitation could we see it as an opportunity? By deconstructing live crowd noise, we can gain a more nuanced understanding of how it contributes to the game experience. Additionally, by exploring diverse approaches to reconstructing crowd noise, we can envision new forms of player and fan engagement that could remain relevant even beyond the current crisis.

Much as every city has its own soundscape, each sport has its own noise culture — think of continuous singing at a soccer game or the alternation between reverential silence and enthusiastic applause at a tennis match. And within each sport, each team’s supporters have their own crowd noise identity tied to local culture as well as to the acoustics of their home venue — think of the Iceland national soccer team’s thunderclap. These sonic identities are rich and varied in content as well as in meaning and can both unite and divide, a fact that leagues, venues and broadcasters, should consider as they plan to introduce artificial soundscapes.

By studying noise levels at different American football stadia, we learned how different team’s fan groups respond to action on the field and how the architecture of stadia can improve crowd noise feedback and engagement. Getting the nuances of the soundscape right can motivate players on the field and keep fans engaged at home. Getting it wrong at best will turn the crowd into background noise and at worst turn people off by its inauthenticity.

The sum of spectators’ cheering creates a continuous white noise that masks quieter sounds and provides cover for strategic communication between players and coaches. In the US, football fans can create a home advantage by drowning out the away team’s snap count.

In the absence of live crowd noise, on-field communication has become unmasked. If we introduce artificial crowd noise into stadiums for its masking function, how much noise should we add back and how will it affect this strategic balance of the game?

We lack solid evidence that noisy supporters improve their team’s chances of winning, but statistical analysis and lab studies have shown that crowd noise does in fact distract and influence referees in favor of the home side. Live fans act spontaneously, so this asymmetry could be considered an authentic part of the game. But if we introduce artificial crowd noise into a venue, who gets to decide how distracting the home side is?

Prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, crowd noise was a spontaneous and organic product of thousands of individual fans. Now that it has become a design challenge, how can we maintain, adapt or even improve on how it motivates, masks and distracts?

Can we reshape sound inside a stadium?

One key decision is whether to reintroduce noise into stadiums or only add it to broadcasts. Adding noise to a stadium has the potential to motivate players and maintain strategic balance as well as create a shared acoustical environment for players and fans.

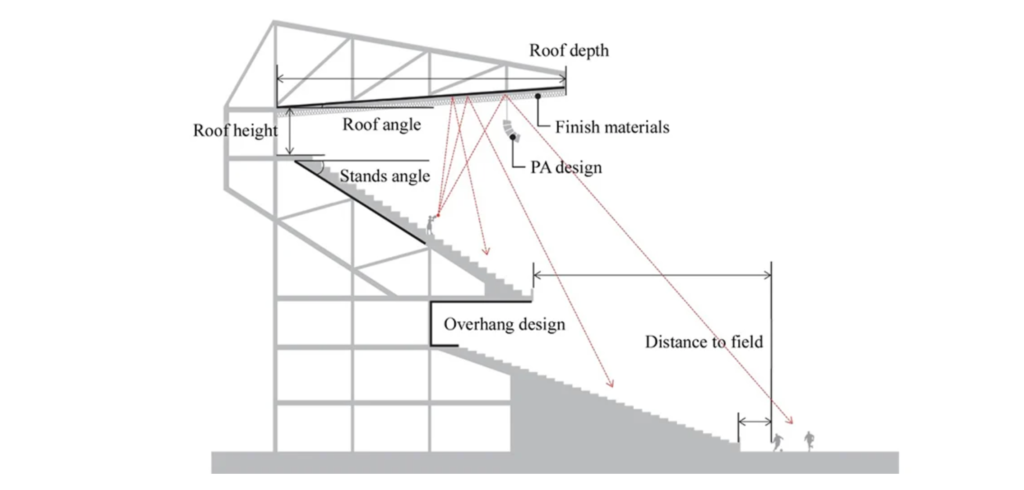

One technical challenge of adding noise to stadiums is that existing public address loudspeakers point towards the stands rather than towards the field. Mimicking fan noise could require reorienting them or adding a secondary sound system.

We have previously investigated how to optimize architectural elements to reflect and amplify crowd noise in new stadiums. Could we modify the design of existing stadiums to optimize artificial crowd noise for the players on the field? When we renovate concert halls, we can add panels above the stage to reflect sound back down to the musicians, allowing them to hear each other better. Perhaps we could add temporary architectural elements in a stadium to reflect sound from existing loudspeakers back down to the field.

Can we design a more captivating soundscape?

Whether it’s played inside a stadium or only on a broadcast, designing the soundscape to a game presents challenges and opportunities. We have already seen some experiments result in issues with audio quality and latency. To avoid falling into an auditory uncanny valley, artificial crowd noise needs to be either abstract enough to not sound like real people cheering, or realistic enough to sound spontaneous, natural and immediately responsive to the game play.

If realism is the goal, we can learn from our experience simulating the 3-D soundscapes of other types of venues. From simulating offices, museums and transit concourses in the Arup SoundLab, we found three things critical to realism. First, it’s important to strike the right balance of background din to foreground activity to convey a sense of scale. Second, we need to avoid recognizable foreground sounds that will give the simulation away if looped. Third, foreground sounds must be appropriate to a specific place, whether that is office conversation appropriate to a company’s specific industry or the unique songs, cheers, and ebb and flow of a specific team’s fans.

In order to achieve a truly engaging, compelling, and inclusive sound experience, holistic, interdisciplinary design intelligence is required to address issues of latency, microphone and signal quality, ambient background noise and acoustical variability from living room to living room, along with the challenges of mixing all the voices together and playing them into stadiums. We may be able to address some of these issues by using artificial intelligence and machine learning to respond to data from fans watching in real time. Could we create a crowd soundscape driven by live, spontaneous fan engagement but constructed from high-quality, spatialized audio samples?

Can we increase access and engagement?

Seeing, hearing and cheering in a stadium is very different from watching a game at home, where one can only witness and not contribute to the atmosphere. The current living-room-only viewing has flattened the fan experience, giving us the opportunity to more equitably include all fans, and perhaps engage new fans, in the experience of the game. Could we add new voices to a virtual crowd from people who can’t go to a physical stadium due to disability, geographic distance or inability to pay for a ticket? Could we give fans a greater stake in the game’s outcome by crowdsourcing noise levels to play in the stadium? Practices like these would ultimately benefit leagues and teams by bringing new fans into the fold and allowing them to participate in a more engaging home watching experience.

While we could see the absence of real-life fans in the stands as a temporary problem to fix and forget once things are back to normal, we could also see the challenge as an opportunity to enhance and highlight the acoustical aspects of sporting events as part of a post-COVID new normal.

The future of crowd noise

The present moment of silence also allows us to question assumptions about crowd noise and its impact while designing solutions to meet the immediate and longer-term needs of live sports. We don’t know when we might again find ourselves in a situation where sporting attendance is limited. By developing tools, techniques, and new forms of experience to respond to the current crisis, we have an opportunity to enable more continuity in the future. We can also examine opportunities to extend the privilege of a live sports experience, maintaining the magic of a stadium while simultaneously transforming remote, passive spectators into active participants, This combination of solutions has the potential to not only solve the challenge of socially distanced live sports but also outlive the pandemic and fundamentally extend a sport’s reach and impact.

This article is attributed to:

Willem Boning – Senior Consultant, Arup

Elizabeth Valmont – Associate Principal, Arup

Matthew Wilkinson – Associate, Arup

Brendan Smith – Senior Consultant, Arup