From earthquakes to sliding football pitches and even building in cardboard, the challenges of modern stadium construction are many and varied. Rob Amphlett, a partner at engineering consultancy Buro Happold, explains how they can be overcome.

Here, looking back over his company’s illustrious portfolio, he picks out some of the projects that have required the development of new techniques and explains the challenges of building new stadia in a rapidly changing world.

From multipurpose venues and redevelopment schemes to projects requiring tricky building materials such as glass – and even cardboard – Happold highlights the previous experiences that can help anyone building for tomorrow

Budgets and time frames are the bottom line of stadium delivery. How can they shape a build and how do you keep on top of them?

Stadia delivery is unique. In no other sector do you have such definitive deadlines to complete and open projects.

For instance, football stadiums need to be completed ready for the start of a new season, and Olympic stadiums have a fixed immovable start date.

This means programme and phasing is everything, and this shapes project designs.

Alignment of budgets to a brief is a key challenge, and yes, they do absolutely shape the original design or plans for refurbishments. However, large scale projects do generally go over budget, but this is often by design.

At Tottenham Hotspur FC’s (THFC’s) new stadium in north London, for example, we started with a modest initial design and then, as the potential for additional revenue was unlocked by the club, we evolved the stadium’s design with the client.

We have also seen a change in the type of stadium work our clients are requesting.

While many are building entirely new stadiums, we are increasingly receiving requests to help with phased redevelopments. This approach sees owners upgrading a stadium section by section, allowing teams to keep playing and venues to continue hosting events.

This is becoming an increasingly popular approach for football clubs. It also helps spread the cost of redevelopment and of course plays a significant role in the designs we develop.

For stadia located in extreme environments how can engineering help enable the venue to operate safely?

Extreme or changing environments are key constraints when considering new building designs.

As engineers, it’s our job to work around them and find solutions, which often means a new or bespoke approach and some innovative thinking.

In extreme heat, for example, stadiums are often open to the sun, external air and wind which makes cooling them particularly difficult.

New stadiums in very hot climates now include systems that circulate cool air mechanically throughout the building. To do this you create plenums – air distribution boxes – under seating tiers, which are pressurized with cool air to be released below the spectators.

For the Fisht Olympic Stadium in Sochi, Russia, which we engineered and is built in a seismic activity zone, we faced significant challenges.

Here, safety was a clear priority as the stadium structure needed to be robust enough to withstand an earthquake.

Generally, the approach is the same with all climate challenges. It’s critical to be clear on what the challenges are and methodically work through them to provide solutions for our clients.

Has there been one famously tricky build that you’ve worked on that you can discuss?

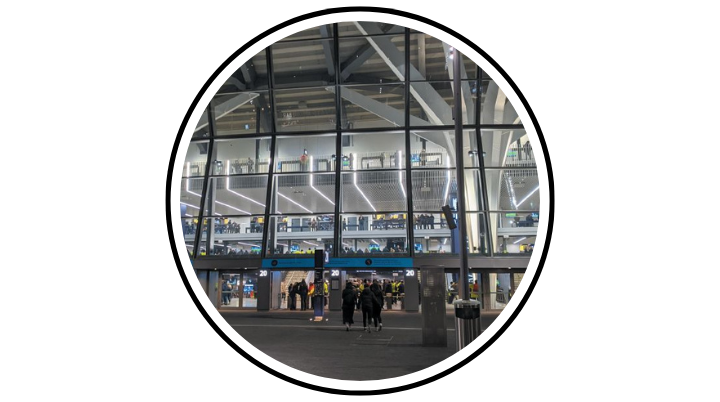

As stadia are bespoke projects, each present their own opportunities and challenges. At THFC, at the request of the club, we devised an innovative retractable pitch so the stadium could host both football and NFL [American football] games.

Providing the facilities and infrastructure for two entirely different sports requires a huge amount of clever, holistic design, considering every detail.

In American football they have a huge number of players who all stand at the side of the pitch.

This may sound trivial but in order to avoid compromising the sight-lines and fan experience, we had to have a second pitch at a lower level and this inspired the sliding pitch solution we adopted.

By sliding the upper grass pitch used for football out, we could provide an artificial 3G pitch for NFL 1.5 meters below.

Similarly, the quality of the playing surface is vital for Premier League and Champions League football, and so was a key requirement of the club. Having a second pitch for NFL avoided damage to the grass football surface and any unsightly white lines left over from NFL.

As a result, the key engineering challenge of the project was how to slide the pitch and make it fit below the huge 17,500-seat home stand.

The innovation here was to split the pitch in three and provide massive transfer structures to span over the sliding sections – the most visible of which are beneath the iconic tree structures you can see through the south stand glazed façade.

Ultimately, while a challenge, we delivered something that has never been done before.

How much of an impact is the rising cost of materials?

The rising cost of materials of course has an impact on projects, but there are ways to minimise this or balance out overall budgets.

Using lower cost or fewer materials is a go-to approach to dealing with cost inflation. And this has become a particular focus as we’ve looked more carefully at sustainability and embodied carbon.

We now monitor all our projects very carefully for embodied carbon. To take an example, Buro Happold engineered Queens Park Rangers’ new training ground, and with a few focused changes we were able to make a huge difference to the amount of embodied carbon used on the project.

This has dual benefits because it allowed the club to build in a more sustainable way, and to save money because lowering the embodied carbon resulted in a deduction in the club’s environmental tax bill.

As we look to the future, materials with lower embodied carbon will become more widely used. Even if the materials may cost a bit more, they can result in huge savings from reduced carbon taxes.

What is the most difficult material to work with and why?

Glass is often the most difficult material to work with and is of course a preferred material in stadium design. It takes a lot of thought and engineering to use, particularly when trying to complete complex designs.

At Jewel Changi Airport in Singapore, another Buro Happold project, we used more than 9,000 individual double-glazed glass panels.

Projects like that then allow us to take this expertise to stadia projects, to help realise ever more intricate designs.

A slightly more left-field example is the work we completed on the Japan Pavilion [for Expo 2000 in Hanover].

Japanese architect Shigeru Ban Frei Otto, inspired by the cultural resonance of Origami in Japan, wanted to create cardboard structures.

This was challenging for several reasons, not least because when under load glue slips over time. With continued testing, refining our design and introducing wood arches, we were able to create a building that stayed true to the initial architectural vision.

Fortunately, our clients in sports and entertainment haven’t asked us to create a cardboard stadium yet!

What type of terrain is hardest to build on and what solutions are required?

One of the most difficult projects we’ve worked on was the London Olympic site, because of the initial groundwork needed.

We spent two years before main construction cleaning the area, which was highly contaminated and unstable. Really, the aim is getting the ground to a state that it will support conventional foundation solutions.

On another site in Manchester we had to pre-grout the entire site, filling in mine works and shafts to create a base that can bear structural loads.

This work is amongst the most challenging because you can never really know what’s under the surface.

You of course carefully consider your designs and construction methods, but you only ever find out what’s underground once you start building.

In this situation, site monitoring becomes critical to learning about the terrain and adapting your work accordingly.

In what ways do building regulations and building controls impact your role?

Building controls play an important role and are there to maintain high standards and keep us all safe.

Complying with them is necessary but not being a slave to codes is key to the engineer’s role.

Realising our innovative designs often requires following more than just building codes.

We must think back from first principles and provide evidence that our solutions meet the key aims of both the codes and our clients’ briefs.

With stadia in particular, building control is focused on the fan experience.

The safety of those attending events is critical and we work in conjunction with local authorities to ensure not just that the stadiums are built to a high safety standard, but that suitable security and crowd management measures are put in place.

This is symbolic of our whole approach to building regulation and control. To use an example, at THFC we were trying to do things that required significant innovation and expertise.

In these instances, it was about collaborating with building control to demonstrate that what we were proposing met with the ethos of the codes.

How do you overcome the new challenges of modern architecture?

A lot of the work we do with high-profile architects involves challenges.

Generally, an architect will develop a vision which needs careful consideration to realise.

In stadia, these challenges are particularly relevant because the project is more than just a functional covering or a provision of seats and functional spaces.

Stadia must often also be a visual representation of an organisation or sports club’s brand; or, in the case of an Olympic stadium, an expression of a message a country what’s to share with the world.

Therefore, achieving the architectural vision is hugely important. THFC wanted it to reflect their position at the pinnacle of English football, so it was about bringing that to life in visual form through a groundbreaking project.

“Japanese architect Shigeru Ban Frei Otto, inspired by the cultural resonance of Origami in Japan, wanted to create carboard structures… Fortunately, our clients in sports haven’t asked us to create a cardboard stadium yet!”

How difficult is it to accommodate super-sized video boards and centre-hung systems, which seem to get bigger every year?

From a core engineering perspective, screens and sound systems are considered an additional structural load that needs to be factored into the design. In this way, incorporating them isn’t overly complex. An additional consideration however is sight lines so that technology enhances, as opposed to hinders, the fan experience.

What is more interesting and possibly more difficult is the integration of this technology into the overall IT system of the stadium.

The real step-change we have seen in the last few years is in terms of integrating all these technological elements into one system. This is about creating a robust system which incorporates entertainment systems, such as videoboards, with security and connectivity.

The future of this is really exciting. At Real Madrid, the club can run all matchday operations remotely from its training ground, without the need to even be in the stadium.